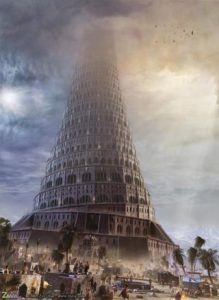

Steven Millhauser’s “The Tower” is a genre of the fantastic that elevates itself to the heavens within the first sentence. As the section within Dangerous Laughter suggests, the story is about the impossible architecture of a tower that reaches and penetrates the heavens. What is interesting, which is seen as well in “The Dome,” is that the narrators explain the complications and solutions of the architecture in an attempt to try to make the story in some sense believable. Furthermore, because the narrator tells us the detailed history of the Tower, we, alongside the narrator, navigate through time and space.

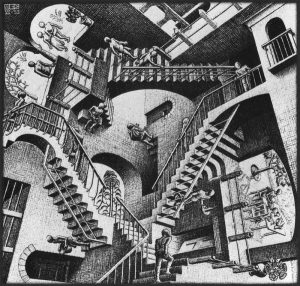

There is also this ridiculous concept of people wanting what they cannot have, the idea that the grass is greener on the other side. Thus, when people reach heaven, they are drawn back to the “plain,” and those who have yet to reach the top keep traveling up, creating this impossible labyrinth where they will never reach where they want to go.

Thus it came about, after the completion of the Tower, that there was movement in two directions, on the inner ramp that coiled about the heart of the structure: an upward movement of those who longed to reach the top, or to settle on a level that would permit their children or their children’s children to reach the top, and a downward movement of those who, after reaching the top, longed to descend toward the plain below, or who, after climbing partway, felt a sudden yearning for the familiar world.

This the narrator deems a “vertical way of life,” and the direct contradiction for those that could not or would not move live the “horizontal life.”

This the narrator deems a “vertical way of life,” and the direct contradiction for those that could not or would not move live the “horizontal life.”

Yet by the end, as the project of the tower is left abandoned, all those in the tower die and eventually go to heaven. Which in a transcending experience is to say that the tower did reach heaven.

Almost every story we’ve read so far by Steven Millhauser in Dangerous Laughter has centered around a modern, suburban town slowly slipping into madness. It may not even have to be the town itself, but rather just the town’s residents. In the short story “Dangerous Laughter”, we witness a small town fixated on this idea of laughter (and later weeping). “The Room In The Attic” ends with our narrator questioning if the girl he’d been talking with ever really existed. Even in “The Disappearance of Elaine Coleman”, a town obsessed with finding this woman and what happened to her, doesn’t care more than the narrator himself. Finding her becomes more important than ever, only to reach the conclusion that they were the reason she vanished. Quite an uncommon reason. Could it be metaphorical, or could it be madness?

Almost every story we’ve read so far by Steven Millhauser in Dangerous Laughter has centered around a modern, suburban town slowly slipping into madness. It may not even have to be the town itself, but rather just the town’s residents. In the short story “Dangerous Laughter”, we witness a small town fixated on this idea of laughter (and later weeping). “The Room In The Attic” ends with our narrator questioning if the girl he’d been talking with ever really existed. Even in “The Disappearance of Elaine Coleman”, a town obsessed with finding this woman and what happened to her, doesn’t care more than the narrator himself. Finding her becomes more important than ever, only to reach the conclusion that they were the reason she vanished. Quite an uncommon reason. Could it be metaphorical, or could it be madness?

The domes in “The Dome” are all obvious metaphors for isolationism, but the underlying implication is that isolation is something to be feared; at one point, the phrase “hostile apartness” is even used. Solitude happens to a staple of fantastical fiction; often, there is one character or a place that is separate from the rest and is consequently treated with suspicion or fear. Sometimes, these fears prove to be unnecessary; the person or place turns out to be perfectly normal if a bit strange. Other times, these instincts are correct—the person or place is something to be feared.

The domes in “The Dome” are all obvious metaphors for isolationism, but the underlying implication is that isolation is something to be feared; at one point, the phrase “hostile apartness” is even used. Solitude happens to a staple of fantastical fiction; often, there is one character or a place that is separate from the rest and is consequently treated with suspicion or fear. Sometimes, these fears prove to be unnecessary; the person or place turns out to be perfectly normal if a bit strange. Other times, these instincts are correct—the person or place is something to be feared.

With much talk of this story has been compared to Anne Frank’s diary and the holocaust, I would also like to point out that the Japenese have been through very similar struggles. During WWII, there were Japanese internment camps. Franklin Roosevelt created these camps as a reaction to the Pearl Harbor bombing in the earlier stages of WWII. Since this book is translated from Japanese, it leaves me to believe that the coping of the genocide is prevalent years prior.

With much talk of this story has been compared to Anne Frank’s diary and the holocaust, I would also like to point out that the Japenese have been through very similar struggles. During WWII, there were Japanese internment camps. Franklin Roosevelt created these camps as a reaction to the Pearl Harbor bombing in the earlier stages of WWII. Since this book is translated from Japanese, it leaves me to believe that the coping of the genocide is prevalent years prior. throwing us into the fantastic circumstances of this reality, it slows down the events as they are told. In short stories, readers get to speed through a story and not get all the necessary details. However, an article of the fantastic that is extremely important is that no one has a name. This entire book is about loss and censorship of knowledge. No one is given a name. Not the narrator, the editor, or the old man. The narrator is a writer; writing is all about the identity of characters and events. Names are also about identity. Losing your name strips away a part of you, not just in a figurative sense, but in a literal one. If one is introducing themselves, yet not allowed to say their name, how is one to explain who they are? So much of one’s identity is attached to a name. Even concepts without a name hold no meaning. “On the other hand, one of the perks of the job was that I received gifts of food from some of our clients, like sausage and cheese and corned beef, which had long since vanished from the markets and were an enormous treat for the old man, R, and me.” (pg. 164) The control over the lost items — books, perfume, birds — is what the narrator wants. Censorship is dangerous in both forms in this book. Censorship shows through the text. The fiction bleeds into reality. Where the government censors what we know, the difference is what is forgotten from the story ceases to exist in their world. The Memory Police enforce the forgetting of items; they make sure that no one remembers things they aren’t supposed to.

throwing us into the fantastic circumstances of this reality, it slows down the events as they are told. In short stories, readers get to speed through a story and not get all the necessary details. However, an article of the fantastic that is extremely important is that no one has a name. This entire book is about loss and censorship of knowledge. No one is given a name. Not the narrator, the editor, or the old man. The narrator is a writer; writing is all about the identity of characters and events. Names are also about identity. Losing your name strips away a part of you, not just in a figurative sense, but in a literal one. If one is introducing themselves, yet not allowed to say their name, how is one to explain who they are? So much of one’s identity is attached to a name. Even concepts without a name hold no meaning. “On the other hand, one of the perks of the job was that I received gifts of food from some of our clients, like sausage and cheese and corned beef, which had long since vanished from the markets and were an enormous treat for the old man, R, and me.” (pg. 164) The control over the lost items — books, perfume, birds — is what the narrator wants. Censorship is dangerous in both forms in this book. Censorship shows through the text. The fiction bleeds into reality. Where the government censors what we know, the difference is what is forgotten from the story ceases to exist in their world. The Memory Police enforce the forgetting of items; they make sure that no one remembers things they aren’t supposed to.  In The Memory Police, things began to disappear from the unnamed island, along with the communities’ memories associated with the item. However, they do not seem to miss the items, let alone dwell upon their loss. In the beginning, the narrator describes a scene of her and her mother, when she was alive. Her mother was not like the other people in the community, she remembered the items that disappeared, and even housed them in a secret compartment of her studio. She was a sculptor. Her mother is tricked and killed for her memories of the banned objects. Her father was an ornithologist and died before the birds disappeared.

In The Memory Police, things began to disappear from the unnamed island, along with the communities’ memories associated with the item. However, they do not seem to miss the items, let alone dwell upon their loss. In the beginning, the narrator describes a scene of her and her mother, when she was alive. Her mother was not like the other people in the community, she remembered the items that disappeared, and even housed them in a secret compartment of her studio. She was a sculptor. Her mother is tricked and killed for her memories of the banned objects. Her father was an ornithologist and died before the birds disappeared.

e one who understands what art and writing can be. He insists on saving as many books as he can when the novels disappear and insists that she continue with her manuscript even after the novels are gone. When she herself is disappearing, he tells her that “Each word you wrote will continue to exist as a memory, here in my heart, which will not disappear.” (270) And isn’t it true that every poem or book we read and every piece of art we look at stays with us in a way? It is hard for something to truly disappear when put to words or image and it makes me think a little more about why art in all forms is usually the first thing silenced when times are dark.

e one who understands what art and writing can be. He insists on saving as many books as he can when the novels disappear and insists that she continue with her manuscript even after the novels are gone. When she herself is disappearing, he tells her that “Each word you wrote will continue to exist as a memory, here in my heart, which will not disappear.” (270) And isn’t it true that every poem or book we read and every piece of art we look at stays with us in a way? It is hard for something to truly disappear when put to words or image and it makes me think a little more about why art in all forms is usually the first thing silenced when times are dark. Though many may handle it differently, the idea of loss penetrates our bubbles of happiness when we least expect it. On an island, a group of people named The Memory Police will take things at random from the world. When that item, idea, or person is removed, so are the memories that remind them of what was lost. Though the novel can be read as political (the government is taking over our lives), it can actually read as the tale of death and loss.

Though many may handle it differently, the idea of loss penetrates our bubbles of happiness when we least expect it. On an island, a group of people named The Memory Police will take things at random from the world. When that item, idea, or person is removed, so are the memories that remind them of what was lost. Though the novel can be read as political (the government is taking over our lives), it can actually read as the tale of death and loss.