Garcia Marquez weaves countless varieties of the fantastic into the first forty pages of his novel. Starting from the opening line, we are given both future and past at the same time. “Many years later,” we are told, “as he faced the firing squad, Colonel Aureliano Buendia was to remember that distant afternoon when his father took him to discover ice.” Such an intriguing and captivating line as well as a hint that Garcia Marquez will often change from past, present, and the future as the story unfolds.

Garcia Marquez weaves countless varieties of the fantastic into the first forty pages of his novel. Starting from the opening line, we are given both future and past at the same time. “Many years later,” we are told, “as he faced the firing squad, Colonel Aureliano Buendia was to remember that distant afternoon when his father took him to discover ice.” Such an intriguing and captivating line as well as a hint that Garcia Marquez will often change from past, present, and the future as the story unfolds.

The obsession of Jose Arcadio Buendia with the sciences transforms him from a youthful patriarch of the village into a madman. As is told on page nine, “…pulled away by the fever of the magnets, the astronomical calculations, the dreams of transmutation, and the urge to discover the wonders of the world…from a clean and active man…changed into a man lazy in appearance, careless in dress, with a wild beard.” It’s such a drastic, unbelievable change in both appearance and nature that the townspeople think he is under a spell.

The clairvoyance of Aureliano described on page fifteen is another example of the fantastic that adds mystery to the story. As Aureliano says from the kitchen, “It’s going to spill.’ The pot was firmly placed in the center of the table, but just as soon as the child made his announcement, it began an unmistakable movement toward the edge, as if impelled by some inner dynamism, and it fell and broke on the floor.” Did he really predict the future or was it a coincidence? We have no reason to believe it’s not true.

Even inventions can seem fantastic, as Jose Arcadio Buendia thinks when he first sees the block of ice. Prior to the gypsies bringing it, no one in Macondo had ever seen such a thing. It’s not surprising, then, that solid water would have such an impact on Buendia, especially since he believes it is the answer to his dream about a city with mirrors.

Mutations add another ingredient to Marquez’s Buendia family. Ursula’s aunt, who married Buendia’s uncle, gave birth to a son with a pig’s tail. The family viewed this as a curse because of the cousin relationship between the two, and Ursula is constantly afraid that she herself will bear a child with the same deformation because she and her husband are cousins. Now, did the son really have a pig’s tail or was it simply an unknown medical illness? Common sense tells us that it wasn’t, but we have no solid evidence to prove otherwise.

On page twenty-two, the ghost of Prudencio Aguilar haunts the house of Buendia and Ursula until both decide to leave so Aguilar could have peace. Was there really an apparition or was it simply guilt and a heavy conscience that made them leave the town?

This last example may not seem fantastic, but it’s almost unbelievable that Ursula would be the one to find the route that Buendia had long searched for but could not find. She’s the one who brings their people to Macondo and essentially puts the town on the map as a valuable resource. She hadn’t even been looking for it, but searching for her son. So a mother’s love is what opens the gates of Macondo.

I may still pause and think, “Did that really happen?”, but this class has drilled into me to simply accept the fantastic and enjoy the story.

Garcia Marquez weaves countless varieties of the fantastic into the first forty pages of his novel. Starting from the opening line, we are given both future and past at the same time. “Many years later,” we are told, “as he faced the firing squad, Colonel Aureliano Buendia was to remember that distant afternoon when his father took him to discover ice.” Such an intriguing and captivating line as well as a hint that Garcia Marquez will often change from past, present, and the future as the story unfolds.

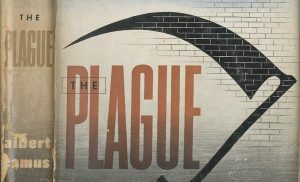

Garcia Marquez weaves countless varieties of the fantastic into the first forty pages of his novel. Starting from the opening line, we are given both future and past at the same time. “Many years later,” we are told, “as he faced the firing squad, Colonel Aureliano Buendia was to remember that distant afternoon when his father took him to discover ice.” Such an intriguing and captivating line as well as a hint that Garcia Marquez will often change from past, present, and the future as the story unfolds. In my email this morning, I asked you to think a bit about the current circumstances we face — the pandemic created by the novel coronavirus, the social isolation being imposed on our society and throughout much of the world, and the myriad ways in which our lives have been abruptly interrupted and altered — and its relation to the topic of this class: the varieties of the fantastic as they appear in works of fiction. The website

In my email this morning, I asked you to think a bit about the current circumstances we face — the pandemic created by the novel coronavirus, the social isolation being imposed on our society and throughout much of the world, and the myriad ways in which our lives have been abruptly interrupted and altered — and its relation to the topic of this class: the varieties of the fantastic as they appear in works of fiction. The website

“Salt Slow” is a heart wrenching account from the woman narrator who recounts the love she has for her partner, which she depicts as an intense love that fades between them as time goes on.

“Salt Slow” is a heart wrenching account from the woman narrator who recounts the love she has for her partner, which she depicts as an intense love that fades between them as time goes on. As the story began, I thought the point of view of “A Very Old Man With Enormous Wings” was very important. The story begins when a supernatural weather occurrence happens and no one knows what is happening. One day, a weak old man is found lying in the mud. Everyone is curious and frightened, but they also have trouble believing that he is a real angel, based on his disheveled appearance. As far as point of view, it seems that the story is written in third person omniscient because even though it follows a specific character, there is also the exposure of other people’s thoughts and reactions, or in third person limited, since the story follows one person and they could simply be seeing the reactions of others. This is interesting because it wasn’t written in first person. Instead, the reader receives many different opinions and actions from the other characters.

As the story began, I thought the point of view of “A Very Old Man With Enormous Wings” was very important. The story begins when a supernatural weather occurrence happens and no one knows what is happening. One day, a weak old man is found lying in the mud. Everyone is curious and frightened, but they also have trouble believing that he is a real angel, based on his disheveled appearance. As far as point of view, it seems that the story is written in third person omniscient because even though it follows a specific character, there is also the exposure of other people’s thoughts and reactions, or in third person limited, since the story follows one person and they could simply be seeing the reactions of others. This is interesting because it wasn’t written in first person. Instead, the reader receives many different opinions and actions from the other characters. The fantastic in “Salt Slow” is not the many sea creatures that appear dead on the surface of the water; it is the size of the sea creatures. There is not one specific element of the fantastic in this story; a few others are the “baby” born, the webbed fingers that grow as the creatures grow, and the abandoned boats/settlements. “Her feet are growing webbed, although they don’t talk about that. Sometimes at night he takes his apple knife to the delicate membranes between her toes, but they don’t talk about that, either.” “Salt slow” shows the distance between people, the couple the story follows, and the distance between their current lives and their past ones. The flooding is a reference to the biblical flood, or at least similar to it. The people left are few and far between, however, the only animals we see as readers is the mythical sized from the boat. We only hear about animals we know as dead or food. Everything in this story has changed except the couple, and even then the flashbacks show the difference in what they had before the flood and after the tide started. Their relationship went from one of passion to one not necessarily of necessity, but one of mutual understanding. “WHEN THEY HAD first fallen in love, she had kissed him with an intensity which imagined him already halfway out the door.” I think this is not only a story of the fantastic, but it is also a type of horror story. These creatures and life on the ocean is the true horror. Her body is transforming to be more sea creatures like, and the “child” she gives birth to is not human. This is a physical transformation, unlike “Metamorphosis,” that was how Gregor felt in his situation. In “Salt Slow,” the change is literal. She is becoming like the creatures below.

The fantastic in “Salt Slow” is not the many sea creatures that appear dead on the surface of the water; it is the size of the sea creatures. There is not one specific element of the fantastic in this story; a few others are the “baby” born, the webbed fingers that grow as the creatures grow, and the abandoned boats/settlements. “Her feet are growing webbed, although they don’t talk about that. Sometimes at night he takes his apple knife to the delicate membranes between her toes, but they don’t talk about that, either.” “Salt slow” shows the distance between people, the couple the story follows, and the distance between their current lives and their past ones. The flooding is a reference to the biblical flood, or at least similar to it. The people left are few and far between, however, the only animals we see as readers is the mythical sized from the boat. We only hear about animals we know as dead or food. Everything in this story has changed except the couple, and even then the flashbacks show the difference in what they had before the flood and after the tide started. Their relationship went from one of passion to one not necessarily of necessity, but one of mutual understanding. “WHEN THEY HAD first fallen in love, she had kissed him with an intensity which imagined him already halfway out the door.” I think this is not only a story of the fantastic, but it is also a type of horror story. These creatures and life on the ocean is the true horror. Her body is transforming to be more sea creatures like, and the “child” she gives birth to is not human. This is a physical transformation, unlike “Metamorphosis,” that was how Gregor felt in his situation. In “Salt Slow,” the change is literal. She is becoming like the creatures below.