Throughout this course we have explored the realm of fantastic in fiction and the amount of varieties within the category. If we were to have read a story about a pandemic that caused mass hysteria and isolation just a couple months ago, before the pandemic became a force to be reckoned with, we would have labeled it as fantastic. Why? Is it because we have never lived through such a pandemic such as the Bubonic Plague, or simply that we haven’t heard of the other viruses that are fatal and have mass media attention?

We have learned in this course that any work of fiction is considered fantastic in the sense that it was created from the mind. However, COVID-19 is very real and it is causing a frenzy throughout the globe. Stores are dried out from mass hysteria caused by the media. Laws were passed in many Northern states against mass gathering, restaurants and small businesses were shut down. Isolation began.

As the pandemic was in its first stages, I couldn’t help but remember the game I used to play. When countries refused to close their borders, airports, ship ports, I shamed them. I would say, “I literally played an app that mimicked this whole situation.”

Let’s take a look at the game I’m referencing. In 2012, an application was released called Plague, Inc. It is a game that simulates the entire globe and contains all countries, ship exports and imports, as well as airplane exports and imports. It is a “real-time strategy simulation game” in which the player must create a pathogen, virus, bacteria, or fungus and the sole objective is to develop the pathogen into a deadly pandemic and exterminate all living creatures (in this case, it is concentrated on humans) on planet earth. When the player reaches to “0” for human population, that is when the player wins the game and their pathogen is successful. Basically, this game was designed to show the CDC, Centers for Disease Control, how easy it is for one outbreak to overtake the human population if we do not follow the right precautions (washing hands regularly, not taking small illnesses seriously, etc.) This app became widely popular and even was runner up to the IGN Game of the Year 2012 awards for “Overall Best Strategy Game.”

In height of the Coronavirus pandemic, Plague, Inc has seen a soaring sales increase since 2012 and even more than the Ebola scare, as well, in 2014-2016. In China, Plague, Inc. was in the number one spot for best paid app in the app store before the government banned it on 27 February 2020 for “illegal content.” There was no further explanation as to why it was banned in China. An explanation is given to justify the amount of sales and booming popularity of the app now, in the height of the COVID-19 pandemic, for China. The explanation simply states that it was bought and downloaded so that the people of China can better understand and deal with their fears with this virus. Maybe if they pretended it was all part of a game, it wouldn’t feel as real?

As I have examined numerous news articles on this pandemic (it seems as though it has taken over not only the world, but every news station as well) I note that the fantastic is not what the media reports and the mass hysteria, but what COVID-19 has done to the world in relation to human isolation. In Venice, Italy, the entire place is on lock down. Nobody can walk the streets but instead must stay in their houses or apartments in quarantine. Since the lock down, it has been reported that the canals have been crystal clear, not polluted, and fish have returned to the canals. It seems as though COVID-19 and its regulation to isolate and quarantine is healing the earth, or returning things to the way it was before human development and interaction.

Self-isolation could be leading to a large reduction in airborne Nitrogen Dioxide

While the world grapples with the novel coronavirus, the pandemic is having some unexpected but positive side effects. The slowdown in human activity due to the pandemic, has so far been shown to have had a positive impact on the planet.

With large parts of Italy on lockdown, pictures have emerged on a Facebook group, Venizia Pulita (Clean Venice), of Venice’s canals showing signs of improvement. Usually very murky waters, the canals have become much clearer, to the extent that the fish living inside are now visible. Not only are the fish visible, white swans have now replaced the famous gondolas, floating across the cleaner waters. There are also reports that dolphins are now swimming in the canals, too.

In China, where the first cases of coronavirus were detected, a massive decline in pollution and greenhouse gases have now been recorded.

In conclusion, I believe that COVID-19 is not fantastic as it is a pandemic taking the world by storm, but it is actually helping the planet heal from years of a human’s abuse to the environment. The isolation we are currently captive within may seem boring and dull, but it is actually helping the planet.

Sources:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Plague_Inc.

https://www.gqmiddleeast.com/culture/is-the-coronavirus-lockdown-actually-healing-the-planet

(I highly recommend the link posted above! It is a very good read and gives a little light to the situation we are facing. It even includes videos of cute dolphins swimming in the canals.)

Also, here are some other links that are good reads, but I did not include in my blog post if you want something positive to read about this pandemic.

https://www.dailymaverick.co.za/opinionista/2020-03-17-covid-19-planet-earth-fights-back/

https://www.bbc.com/news/science-environment-51944780

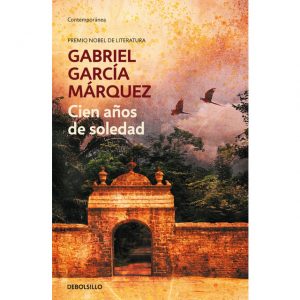

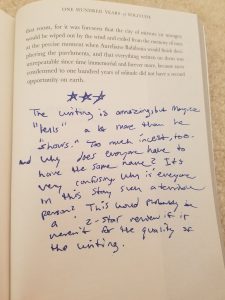

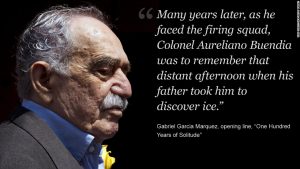

I enjoyed this book. It did take me time to read it, and there were parts that I had to re-read because of the timeline jumping, but I liked the imagery and storyline. Out of all of the notes I made inside the book, this particular statement in the back summed it all up for me. As the New York Review of Books once said, “[Gabriel Garcia Marquez] forces upon us at every page the wonder and extravagance of life.” Which I agree with.

I enjoyed this book. It did take me time to read it, and there were parts that I had to re-read because of the timeline jumping, but I liked the imagery and storyline. Out of all of the notes I made inside the book, this particular statement in the back summed it all up for me. As the New York Review of Books once said, “[Gabriel Garcia Marquez] forces upon us at every page the wonder and extravagance of life.” Which I agree with. We have deemed this loss of time and type of isolation elements of the fantastic. However, I would argue that Gabriel García Márquez has managed to tell us the story of not only Colombia’s history but the history of many Central and South American countries. Of which were contempt living as they were before tourism, business, and conquistadors decided they could “help.”

We have deemed this loss of time and type of isolation elements of the fantastic. However, I would argue that Gabriel García Márquez has managed to tell us the story of not only Colombia’s history but the history of many Central and South American countries. Of which were contempt living as they were before tourism, business, and conquistadors decided they could “help.”

This morning I came across a brief article online about social distancing and its relation to Yoko Ogawa’s The Memory Police. Published at Slate, the article is titled

This morning I came across a brief article online about social distancing and its relation to Yoko Ogawa’s The Memory Police. Published at Slate, the article is titled